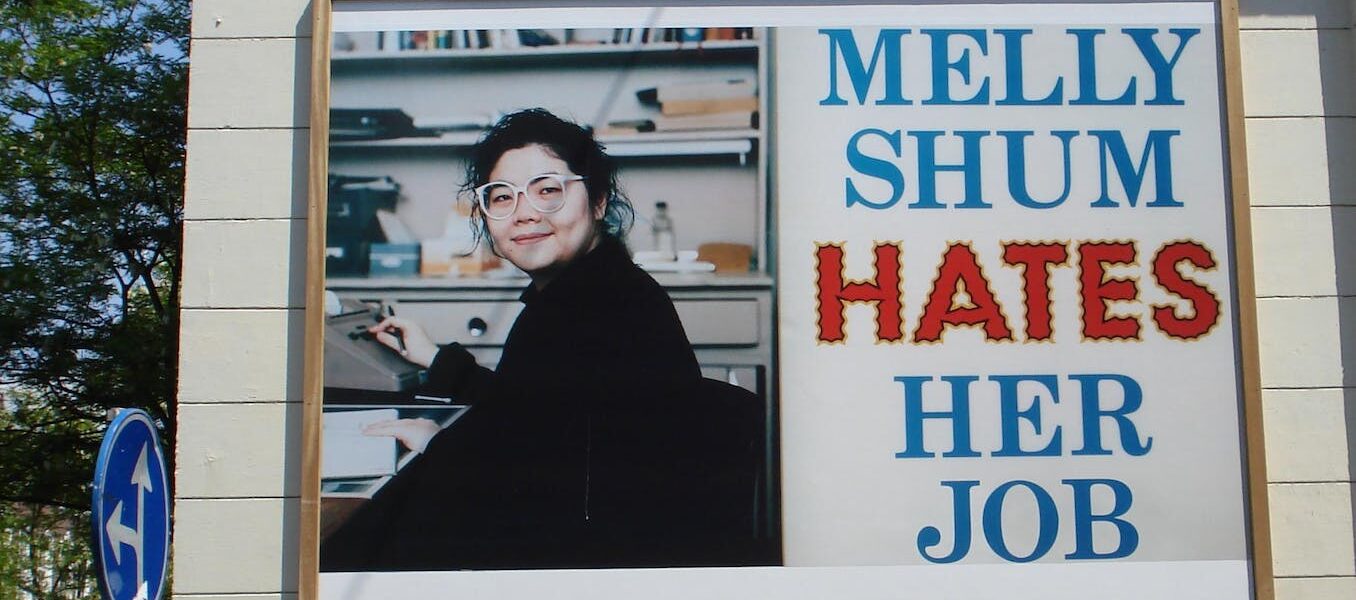

Sure, she’s smiling. But the tired eyes, cramped desk and limp hand on dated office gear tell another story: Melly Shum hates her job. Perhaps she works in what anthropologist David Graeber has in mind in his book Bullshit Jobs?

Yet, 30 years ago, she was launched into a peculiar art world notoriety that recently took a startling turn. Melly Shum Hates Her Job is the name of acclaimed Canadian artist Ken Lum’s 1989 piece that developed an urban public cult following in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and has now inspired the renaming of a museum in that city.

To many viewers, this happened precisely because there’s nothing special about the Melly Shum in this picture: Like many people, she is stuck in a soul-destroying, Sisyphean grind with no obvious way out. As Lum notes, the red, vibrating “HATES” speaks of “the frustration of Melly Shum even though the voice of the text is ambiguous.”

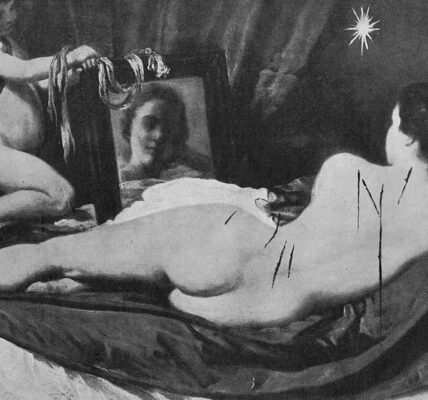

There’s a tradition of artists highlighting everyday heroism, like when Edouard Manet and the Impressionists depicted the streets and bars of the 1870s or American artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles shook hands with 8,500 New York City sanitation workers a century later.

When Lum produced this image as part of his remarkable “Portrait-Logo” series, he drew on that lineage.

But he also took his cue from background and family experiences that he describes in his recent essay collection, Everything is Relevant: the 12-hour days he spent picking strawberries with his mother in fields outside of Vancouver; his grandmother’s decades of toil in a New York City garment factory.

Perhaps that lived experience explains some of why this image struck a chord.

Many of Lum’s pieces zero in on tensions between appearances and meaning, unsettling viewers’ assumptions and perceptions. The piece has been read both as surprising viewers by representing a universal feeling not with a white person but with a person of Chinese descent and as raising questions about the specific causes of Melly’s hatred: Does she face racialized, class- or gender-based discrimination in her job or work opportunities?

(Ira Smirnova/Flickr), CC BY

Struck a chord

In 1990, the year after Lum produced the work, he was invited to have a solo exhibition to inaugurate a new gallery in Rotterdam, the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art.

Lum explained to me how the piece gained its iconic status. The gallery wanted to install a version of Melly Shum Hates Her Job on the building’s exterior to promote the show. “For whatever reason, I asked if the image could be just the work, without my name, without the dates of the show or the associated talks and so on,” he said. When the gallery agreed — quite casually — the piece shifted from advertising to monument. And, as monuments do, this one found its public.

When the exhibition ended and the piece came down, the gallery directors received a flood of letters and phone calls asking where it had gone. That’s when, Lum says, the Witte de With inquired about reinstalling the piece.

Lum asked the gallery if “any reasons had been given for wanting the piece back, because it seemed weird,” he recalls. His doubts fell away when the gallery responded that one person had said: “Every city deserves a monument to people who hate their jobs.” His jaw dropped, he told me, “because it was just so good. And I said, yeah, OK. I am totally fine with this.”

Growing popularity

(Simon Fraser University/Flickr), CC BY

In the 30 years since, a lot has changed. Lum has become one of Canada’s most internationally influential artists, with an extensive exhibition history, a Governor General’s Award, an Order of Canada and a named professorship at the University of Pennsylvania.

The Witte de With Center has evolved into a globally recognized institution, while the district where it is located, Witte de Withstraat, has gone from a non-descript strip to one of Rotterdam’s trendiest areas. Today, Melly Shum Hates Her Job has travelled the world to appear in the Dutch pavilion of the Shanghai Expo 2010 and beyond.

Unfortunately, someone else who travelled the world was the gallery’s namesake, Witte Corneliszoon de With. De With was a 17th-century Dutch naval officer who led violent colonialist expeditions on behalf of the Dutch East India Company.

When the gallery took its name from the street fronting the centre 30 years ago, it made some sense as it helped people locate the building, but today it’s embarrassing. The gallery foregrounded this point in 2017, when the centre hosted an exhibition about the Netherlands actively forgetting its colonial history.

Monumentalizing the overlooked

That fall, the organization started a renaming process. Last month it announced that starting Jan. 27, 2021, it will be called the Kunstinstituut Melly.

“I feel that the work belongs more to the community than to me, given that they’ve activated it far beyond what I ever anticipated,” Lum says, “so it makes sense.”

The practice of monumentalizing the overlooked remains crucial to Lum. “I’m both cynical and optimistic,” he tells me. “I see all these museums taking real steps to diversify, but I think of all the artists of colour and difference who gave up. I see the unprecedented breadth of consciousness among so many people, but I see that just the other day the Philadelphia police killed a Black man, Walter Wallace Jr.”

Lum will be at the University of Ottawa for the sixth Annual Stonecroft Foundation Visiting Artist Lecture on Nov. 12, 2020, at 6 p.m., in conversation with Josée Drouin-Brisebois, senior curator of contemporary art at the National Gallery of Canada.

This is a corrected version of a story originally published on Nov. 10, 2020. The earlier story said ‘Melly Shum Hates Her Job’ appeared at the Dutch pavilion at the 2008 Gwangju Biennial instead of at Shanghai Expo 2010.