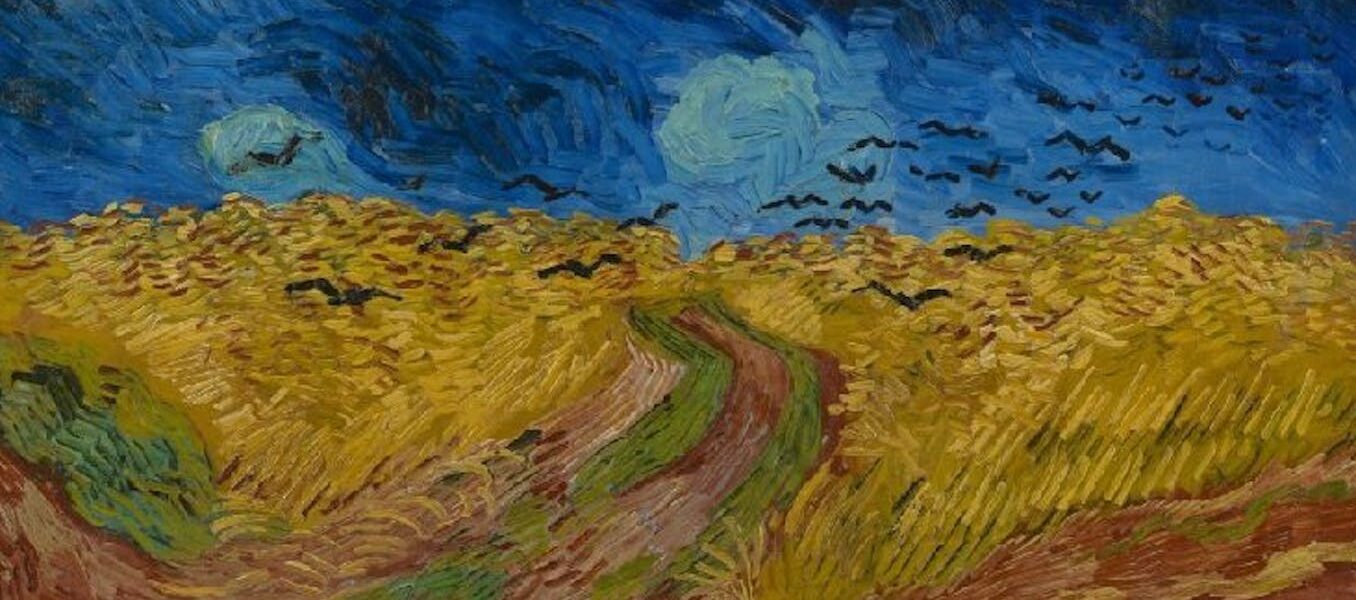

At the time that Vincent van Gogh was creating his acclaimed work, The Starry Night, he was hospitalised at Saint-Paul de Mausole asylum. He painted the vivid night sky from his room without the bars of his window, editing out the institution. Yet, in the case of museums, it is often the institution who edits out the patient.

In collections, objects and stories relating to mental health have largely been presented through a medical model, viewing patients as subjects and silencing their voices.

Where mental health is part of an artist’s story, their creativity may be wrongly credited to their suffering. Often, these narratives sit uncomfortably close to spectacle, an echo of the Victorian freak show in the digital age.

This article is part of our Van Gogh Museum at 50 series. These articles mark the 50th anniversary of Amsterdam’s pioneering gallery and explore evolving cultural perceptions of one of the world’s most famous artists.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, museums are grappling with how best to expose and address biases and gaps in collections and programming.

The Van Gogh Museum first opened 50 years ago. A pioneer of the single artist approach, it formed a keystone of Amsterdam’s tourism strategy.

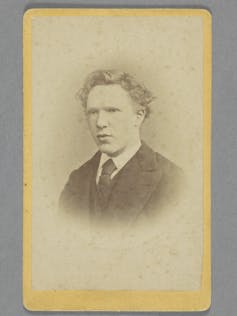

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam / Vincent van Gogh Foundation

Outside of the museum, approaches to mental health (although greatly advanced from van Gogh’s time) were still disempowering. Lobotomies – a Nobel Prize-winning invention in the 1940s – had experienced a post-war boom, but public opinion towards them had become distinctly unfavourable by 1973 after the high-profile death of a patient a few years before.

Throughout his life, van Gogh experienced poor mental health. His complex symptoms caused episodes of intense psychosis, hallucinations and cognitive dysfunction. During one such episode, he famously cut off part of his ear. He died in 1890, by probable suicide.

Van Gogh’s battle with mental health is well known but our perceptions of his story are often less critically evaluated. This highlights a long history of misconceptions around mental health. Since the time of Aristotle, illness and creativity have been thought to be connected. Van Gogh rejected this idea, considering “madness an illness like any other”.

The concept of the “tortured genius”, which sees suffering as a necessary part of creativity, is unhelpful yet deeply embedded. Think of the narratives we hold for Kurt Cobain, Sylvia Plath and Robin Williams.

A 2014 study even discovered that van Gogh’s work was perceived as higher quality by viewers exposed to his mental health story. In promoting suffering over seeking help and recovery, the topic of mental health becomes a spectacle rather than a vehicle for social change.

“Everybody has their yellow paint” – a meme originally posted on social media site Tumblr – neatly illustrates this point by positioning van Gogh as a “beautiful tortured soul” who ate toxic yellow paint to coat his insides with sunshine.

His potential suicide attempt is reframed as a misunderstood quirk. Yet, as tragic stories of social media-inspired self harm demonstrate, the misinterpretation of mental health issues has real impact.

Rethinking mental health

Several institutions, including the Van Gogh Museum, are now working with audiences in order to reevaluate their perspectives on wellbeing.

Van Gogh Museum / Vincent van Gogh Foundation

Discussions between the Van Gogh Museum and young people experiencing mental health vulnerability highlighted the opportunity for the museum to normalise mental illness and to encourage people to seek support where needed.

The community of young people suggested progressive ways for the museum to become a safe space for engagement in which people could tell their own stories.

The resulting project, Open Up with Vincent, has created online and onsite activities such as meditation films, material for school pupils and collaborations with healthcare institutions.

A key part of the museum’s findings was that, in having an uncertain diagnosis, van Gogh’s story resonated with young people as it did not probe his struggles through a medical model. Narratives around his art and life could, instead, open dialogue on mental health and support audiences to consider their own relationships with mental health and wellness.

In the UK, the Tate galleries, working with the mental health charity, Mind, have challenged existing approaches in order to create a more useful dialogue. Finding that 50% of people experiencing mental health problems noted the shame and isolation as worse than the illness itself, they created a more factually accurate portrayal of van Gogh’s mental health through animation. His story becomes a powerful reminder that we should not be defined by our mental health.

As museums develop their institutional perspectives on healthcare from a medical model to a social model, they are evolving into agents of radical change. Co-production with communities has vast potential to develop healthier societies by exploring the intersections of creativity and wellbeing.

The Van Gogh Museum is celebrating its 50th year by “treating audiences” to a “splendid party” and “special activities”, in a nod to the Dutch tradition of being generous to others on your birthday. However, particularly in the context of continued funding crises, we need to be mindful that culture is more than just a “treat.” It is an essential tool in tackling the mental health crisis.