The UK’s biggest prize for contemporary art is back. The 2023 Turner prize shortlist has been announced featuring British artists Jesse Darling, Rory Pilgrim, Ghislaine Leung and Barbara Walker.

An exhibition of the artists’ work will go on show at Towner Eastbourne from 28 September to 14 April 2024 with the winner announced on 5 December.

A prize awarded for an outstanding presentation of an individual artist’s work is not only a chance to pick favourites but an opportunity to discuss the issues it explores, the people involved, the funders, formats and contexts.

My research often focuses on how art and politics have intersected during the past few decades. With a whirlwind 40-year socio-political history this lens can be applied to the prize.

From Thatcher’s 1980s to Channel 4’s 1990s

The Turner prize began in 1984 against the backdrop of Thatcherism. An annual competition to draw media interest and private sponsors made sense in the context of reduced public funding for the arts and an era of competitive individualism.

A civilised affair pitching established painters and sculptors and conceptual artists against each other – the first six winners were white men, as were 28 of 32 the artists shortlisted.

Things changed in 1991 with Channel 4 as a hip new sponsor and a ban on artists over 50. The prize would raise interest in a newly youthful, increasingly fashionable area of UK culture.

The 1990s prizes are remembered for Young British Art. Graduating from art school in the Thatcher era, Young British Artists (YBAs) were well aware of the limited opportunities to build state-funded careers so acted like entrepreneurs and experts in self-promotion.

They staged their own exhibitions in empty warehouses, made “shocking” art with unconventional materials (sharks, dung, unmade beds) and sensational subject matter (pornography, violence, tabloid sleaze). Faux outrage from the tabloid press made artists into household names (Damien Hirst and Tracy Emin).

Much of this felt Thatcherite, but there was something youthful and trendy and edgy about art that jarred with the warm beer and cricket pitches neoliberalism favoured by early 1990s Tories. It sat much more comfortably in New Labour’s

“Creative Britain”.

This was still a nation of entrepreneurial individuals with no interest in 1970s things, like collective bargaining or common ownership of utilities. But Creative Britain was modern and hip – it was Britpop, football and contemporary art.

The televised celebrity-strewn Channel 4 under 50s version of the Turner prize was part of this – feeding the feel-good 1990s vibes, fuelled by PR and underwritten by a debt-driven boom.

2000’s third way

New Labour soon gave up on looking hip – remember the introduction of university tuition fees, deregulated markets and the invasion of Iraq. Some of the tax income from a seemingly buoyant economy was spent on the arts, which were newly redefined as consumer services and required to prove value and efficiency using metrics.

Increased public arts spending provided artists with a sort of freedom. No longer required to whip up controversy or appeal to collectors like Saatchi, Turner prize art came to feel more insularly artistic with abstract painting and installations like light bulbs going on and off.

Occasionally it was political. Mark Wallinger, 2007’s winner, meticulously replicated Brian Haw’s peace camp, which the campaigner had lived in for 10 years in Parliament Square, at Tate Britain.

Titled State Britain, it was created when Tony Blair passed a law to make it illegal to protest within a mile of Parliament. Positioned across the perimeter of the one mile from Parliament no-protest-zone, it probed a line between art and politics.

2008’s financial crash and a new outlook

In 2008, the credit-fuelled capitalism championed by Blair and Thatcher crashed the global economy and the Turner prize couldn’t find a corporate sponsor.

The coalition government formed in 2010 cut arts funding by a third. Shortlisted Turner prize art from that time didn’t say much about austerity or that moment, instead looking a lot like the art of the early 2000s.

For historians Jeremy Gilbert and Alex Williams, the period after the 1990s was marked by a feeling of stasis linked to the widespread acceptance that neoliberal capitalism was here to stay. What Thatcher imposed, Blair accepted. It became difficult to imagine alternatives.

But the art prize was changing as Britain was. Collectives, community and a gentle critique of the traditional Turner prize format all became important.

Anti-austerity movements found a home alongside trade unions in a Labour Party reimagined under the radically social democratic leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. The movement for Black Lives pointed to a history, culture and economy of institutionalised racism.

The 2015 winner, Assemble, were not artists at all, but a collective of architects who worked with communities to create imaginative housing and buildings and resources.

The shortlisted artists in 2019 asked to share the award, using “the occasion … to make a statement in the name of commonality, multiplicity and solidarity” and turning themselves into a collective.

The 2021 shortlist consisted only of collectives, many of which worked with communities in ways that felt more like education or outreach than what some people call art.

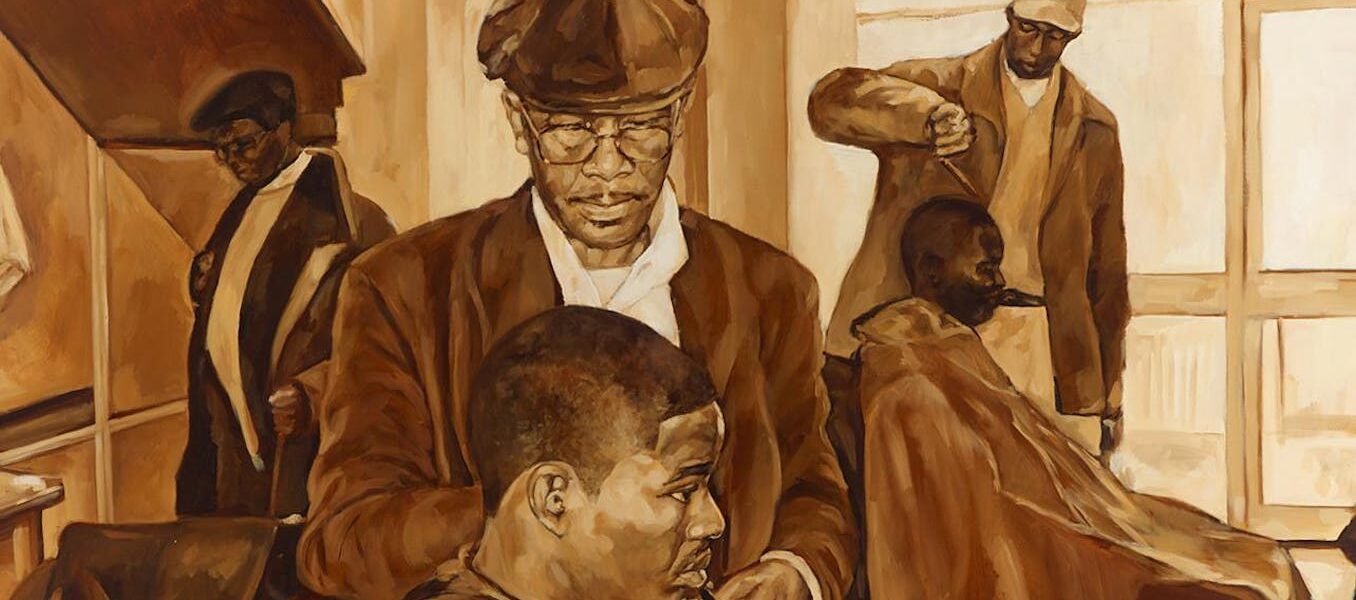

The prize also became more aware of its past limitations, prejudices and oversights. Lubaina Himid, aged 62, was named winner in 2017, after the Turner prize age cap was dropped. In 2022 it was Veronica Ryan, aged 66. Ingrid Pollard, aged 69, was also shortlisted in 2022.

All three had been active since the 1980s, making work that engaged, often playfully and poetically, with colonialism and racism and identity. None of them featured in shortlists from the 1980s or 1990s or 2000s.

The 2023 shortlisted artists share a concern with the experience of hostile, exhausting and strangely fragile systems: the late-capitalist demand to be constantly productive while continually undervalued, the absurd cruelty of bureaucratic governance and the precarity of climates and bodies.

A lot of their art is about the effort to stay afloat or even just to cope. By implication, the work conveys something about the failure of institutions to provide either basic support or transformative change. Hope is found instead in a politics of community and care, vulnerability and interconnection, which offers occasional glimpses of better worlds.