If the National Gallery of Victoria’s 2017 Triennial broke attendance records with more than 1.2 million visitors, it is nothing short of a miracle the 2020 Triennial is taking place at all.

To bring together more than 100 artists, designers and collectives from more than 30 countries, featuring 86 projects, in the era of COVID, was always going to be a tall ask. It has happened and it has a huge “wow” factor with a mixture of major household names as well as completely unexpected, quirky discoveries.

The Triennial 2020 is built around four broad themes with porous borders: Illumination, Reflection, Conservation and Speculation. Even after wading through the voluminous catalogue — more like a piece of bulky furniture than a read-in-bed book — the themes are more like general conceptual props than clear categories.

The concern is with the ability for art to challenge assumptions about the status quo, alert us to impending disasters, suggest alternatives, dazzle us with unexpected inventions and inspire us with wondrous creations of undreamt of beauty.

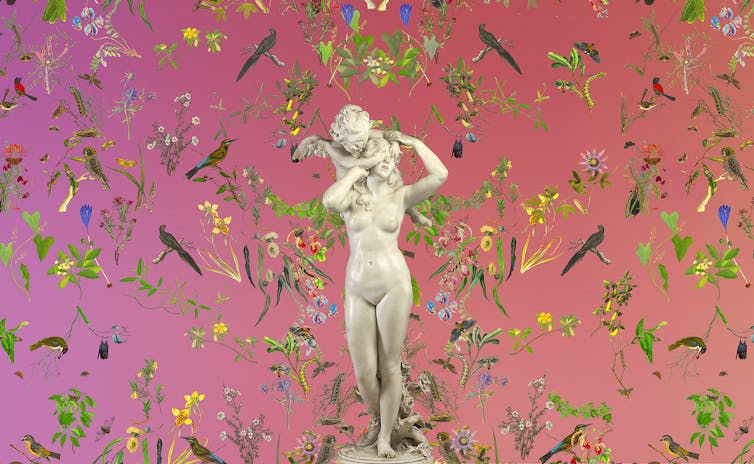

David Allen Burns, American, 1970, Austin Young, American, 1966. Natural History 2020 digital print on self-adhesive polyester fabric. Commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Natural History 2020 is supported by Nicholas Perkins and Paul Banks.

Collection of the artists

A world guided by AI

The one work that had the greatest impact on me was by the young Turkish artist Refik Anadol, now based in Los Angeles. Titled Quantum memories, 2020, it is presented on a huge 10 by 10 metre LED display screen encountered as you enter the NGV building in St Kilda Road.

Commissioned by the gallery, it is a collaborative work between the artist and Google. Employing a dataset drawn from more than 200 million images linked to nature, Anadol uses a Google quantum computer (described as 1000 times more powerful than a conventional supercomputer) combined with machine learning algorithms enabled by AI.

Read more:

Why are scientists so excited about a recently claimed quantum computing milestone?

The image processing algorithms ingest millions of photographs and generate new images with related statistical properties. We are exposed to images of fantastic, ever-changing landscapes that never existed — somewhat uncanny, as if remembering something not previously experienced but somehow convincing and real.

Enthralling, completely seductive and endlessly changing, this work brought to mind the words of the Sufi mystic Rumi, “Don’t grieve. Anything you lose comes round in another form.”

Anadol presents us the world “in another form” guided by artificial intelligence (AI). Unlike a video installation presented on a loop, every moment is a state of flux, constantly reinventing itself and creating new images.

Moving from the high tech to the low tech, we encounter Porky Hefer’s Plastocene – Marine Mutants, 2020, from a disposable world. Hefer, based in Cape Town, South Africa, creates through his Southern Guild fabricators a series of handmade, large-scale environments consisting of imaginary sea creatures from a dystopian future he terms “Plastocene”.

Southern Guild, Cape Town (fabricator). Buttpus designed 2019, manufactured 2020: felted karakul wool, industrial felt, canvas, leather, sheepskin, salvaged hand-tufted wool carpet, recycled PEP stuffing, foam, steel 1512.0 x 1512.0 x 328.0 cm. Frame manufacturer: Streetwires. Felting: Ronel Jordaan Textiles. Sewer & pattern maker: M Clothing. Assembly: Wolf & Maiden Creative Studio. Karakul wool sponsored by Jonay Wool. Carding Commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with funds donated by Barry Janes and Paul Cross, Neville and Diana Bertalli, 2020. © Porky Hefer.

© Porky Hefer Image courtesy of Porky Hefer and Southern Guild

They include a huge, octopus-like creature made from hand-felted cigarette butts. In Hefer’s worldview, the end of the Anthropocene era will be marked by a new species that will transmutate and absorb plastic bags, straws, coffee cups and other pollutants.

Although humans, as we know them, will struggle to survive in this polluted environment, these mutants will flourish.

Read more:

How the term ‘Anthropocene’ jumped from geoscience to hashtags – before most of us knew what it meant

A selfie magnet

If Anadol and Hefer are relatively unknown to Australian audiences, Jeff Koons is one of the most high-profile and iconic contemporary American artists. His Venus, 2016-20, is a two-and-a-half metre, mirror-polished, stainless steel sculpture with colour coating that adds to the Baroque exuberance of the piece.

© The artist and Gagosian

The source image is a relatively obscure 34-centimetre painted, porcelain figurine of the same name by Wilhelm Christian Meyer from 1769.

Koons has taken liberties with his model to heighten the latent eroticism of the forms. As he observes:

Venus represents the combination of understanding the needs of society and of something greater than self, while at the same time the desire for procreation and the continuation of the species. It involves the seductiveness of all the senses — the joys, pleasures and pains of life itself.

This acquisition will certainly become a selfie magnet for the NGV.

Radiating in its space

© Lee Ufan, courtesy Pace Gallery, New York

Another high profile participant in the Triennial is Korean artist Lee Ufan, who employs the Zen Buddhist practice of painting as a form of meditation revealing energy and realisation. His Dialogue, 2017, a major new acquisition for the gallery, is a sublime piece that seems to radiate in its space.

The artist recently observed: “What is light and what is darkness? I do not like the definition that sees existence in terms of light and nothingness in terms of darkness. There is darkness in all forms of light, and light penetrates all kinds of darkness. A concept of light or darkness considered in isolation cannot be valid.”

A meditative, hypnotic painting, it seems to vibrate in space and is in contrast to the loud, bombastic and attention grabbing forms populating the Triennial, which occupies all levels of the gallery building.

synthetic polymer paint on Stringybark (Eucalyptus Sp.), 189.0 x 102.0 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with funds supported by the Orloff Family Charitable Trust, 2020.

© Dhambit Mununggurr, courtesy Salon Indigenous Art Projects, Darwin

It is always difficult to summarise an exhibition like this one, conceived as a series of immersive spaces with superb moments such as the blue paintings and sculptures of Dhambit Mununggurr, the dialogue with the NGV collection by the Fallen Fruit or painting with neon light by the Welsh conceptual artist Cerith Wyn Evans.

The NGV Triennial is being held at a time when the success of exhibitions can no longer be measured by attendance numbers, but it seems to be hitting the right spot.

Victoria’s premier, Daniel Andrews, is allocating a record $1.46 billion for the building of a new NGV Contemporary and another $20 million is promised by the Ian Potter Foundation. The future looks bright for subsequent triennials.

Triennial 2020 is at the National Gallery of Victoria until 18 April 2021.