As spiritualism’s popularity grows, photographer Shannon Taggart takes viewers inside the world of séances, mediums and orbs

The word séance conjures images of darkened rooms, entranced mediums, strange occurrences and spirit voices. For many contemporary audiences, these visions might seem like something out of the past, or perhaps a movie, rather than a living belief system.

For the past 20 years, American photographer Shannon Taggart has explored modern spiritualism, a religion whose adherents believe in communication with the dead.

Her photographic series “Séance,” which was recently on view at the Albin O. Kuhn Gallery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, provides a window into this often misunderstood religion.

As a curator and art historian who has researched apparition photographs and the art of conspiracy theory, I was drawn to Taggart’s images because they offer a lens through which to examine the role of spirituality in modern life.

In an era defined by a global pandemic, heightened political division and the planetary threat of climate change, I wonder: Is spiritualism due for a major resurgence?

Spiritualism comes knocking

Spiritualism emerged near Rochester, New York, in 1848 when two sisters, Kate and Margaret Fox, claimed to hear a mysterious rapping at their bedroom wall. The adolescents claimed to communicate through a system of knocks with the spirit of a man who had died in the house years earlier. News of the phenomenon traveled quickly, and the girls appeared before crowds demonstrating their purported abilities.

Soon, reports of similar phenomena occurring across the United States appeared in the press, and the possibility of speaking with the deceased fueled the popular imagination.

Spiritualism first grew in private. People who channeled communication with the dead, called mediums, operated out of their homes, where they would organize séance circles, gatherings in which a small group attempted to make contact with the spirit world.

Over time, spiritualists started appearing publicly at conventions and outdoor summer camp meetings. By the 1870s, they began to put down roots, founding like-minded communities and centers of study, such as the spiritualist colony of Lily Dale, New York, established in 1879.

In addition to holding séances, spiritualists practice healings and believe in the gift of prophecy. Mediums say they convey messages from the dead to the living, including reports about the future.

Many spiritualists hoped to make utopian visions of the future a reality in the present by supporting progressive political causes such as abolitionism, women’s rights and Indigenous rights.

Notably, spiritualism gave women an unprecedented role in religion, providing an audience and a platform to deliver messages both personal and political. Suffragists Marion H. Skidmore, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony all spoke at Lily Dale. The views of spiritualists thus represented a radical break from traditional religious and political authority.

Ghosts in the machine

The Fox sisters’ purported ability to communicate with the dead became known as “the spiritual telegraph,” referencing the then-recent invention by Samuel B. Morse. As spiritualism developed, adherents embraced technology as tools for spirit communication and to prove the existence of spirits.

Photography became “the perfect medium” with which to create an iconography of spiritualism. Whether it was through astronomical, microscopic or X-ray photography, cameras could render the unseen visible. Despite the proliferation of altered photographs in the 19th century, the photograph’s status as a truthful representation of reality remained – and, one might argue, continues to remain – largely intact.

Photography also played a leading role in the 19th century’s memorial culture, since the camera could freeze time and render absent loved ones present, if only as a visual trace.

The American Civil War brought death at an unprecedented scale into people’s living rooms through the pages of the illustrated press. Black attire, mourning jewelry and the genre of post-mortem photography were commonplace in a culture of grieving.

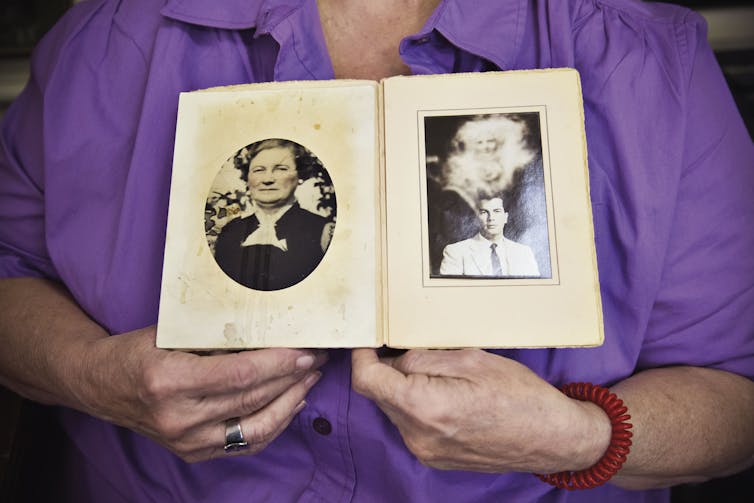

© Shannon Taggart. Courtesy of the Artist, Author provided

In the 1860s, New York portrait photographer William Mumler and his wife, Hannah Mumler, a medium, offered portrait sessions in which spirits of the sitters’ loved ones appeared to manifest in the resulting photographs.

Mumler’s spectacular portraits also raised the specter of hucksterism. The photographer was charged with fraud by claimants who argued he faked the photographs, and none other than showman P.T. Barnum gave evidence for the prosecution.

In the early 20th century, Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle famously rallied to defend British medium Ada Emma Deane, who was also accused of faking spirit photographs.

The double-sided coin of belief and skepticism haunts these historical examples; nonetheless, the psychological impact of these images among the grieving remained powerful.

Spiritualist revivals

History seems to suggest that catastrophic loss of life can spur renewed interest in spiritualist beliefs.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the Mumlers’ portraits became all the rage amid the devastation of the U.S. Civil War, while Deane’s popularity peaked in the wake of World War I and the flu pandemic.

Has the pervading sense of uncertainty induced by the COVID-19 pandemic triggered another spiritualist revival?

Alternative belief structures, including astrology and tarot, seem to have experienced a resurgence, reaching new audiences through the internet and social media.

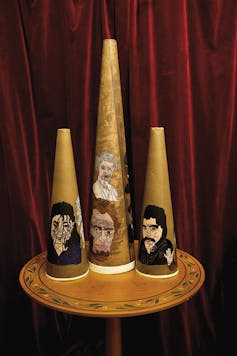

© Shannon Taggart. Courtesy of the Artist., Author provided

Recently, a number of mediums have become famous thanks to their endorsements by celebrity clientele. Some mediums claim to be able to channel stars from the grave, from Louis Armstrong to Elvis Presley.

While modern mediums have their detractors, their eager adoption of television and the internet is a logical step for a religion that has always embraced new technologies.

What was once seen as a niche subculture or the domain of late-night 1-900 call-in shows has gone mainstream: Psychic businesses were a US$2 billion industry in 2018.

Shannon Taggart’s ‘Séance’

This new spirituality has influenced pop culture as well as high art; the Guggenheim’s 2019 retrospective of Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint was the most-visited exhibition in the museum’s history, drawing over 600,000 viewers.

New York Times art critic Roberta Smith argued that the exhibition’s impact amounted to a “psychic and historical shift” in the art world. Smith’s use of the word “psychic” is apt; the exhibition was a watershed not only for restoring to primacy women’s role in the development of abstract painting, but also for re-centering the spiritual within art.

Taggart’s photographs, meanwhile, explore present-day practices, sites and objects of spiritualism.

Allowing chance and automation to guide camera experiments, she reveals processes of transformation and altered states through blurred effects, halos of light and doubling in images that reference historical spirit photographs.

In one image, for example, a grieving mother raises her arms into a darkened sky dotted with circles of light known as orbs. Orb photography is a recent innovation within spirit photography in which practitioners call upon spirits to manifest orbs, which are then captured by digital cameras. Orb photography is another example of the ambiguity of spirit photographs: Does it channel the supernatural, or simply capture reflections of dust on the camera lens?

© Shannon Taggart. Courtesy of the Artist, Author provided

For Taggart, that question is largely beside the point. Her aim is to remain truthful to the psychological experience of spiritualism, to make visible what is ineffable.

Taggart’s photographs recover the marginalized history of spiritualism at a moment when the religion feels once again on the verge of a resurgence.

As Taggart is fond of saying, “You don’t have to take spiritualism literally to take it seriously.”

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]