From the ongoing debacle of the Windrush scandal to the UK government’s dubious race report and the pervasive online abuse endured by Black British footballers – what does it mean to be Black and British today? And what has this to do with our understanding of British history?

No doubt, Black History Month offers some pause for thought. But answers to these perennial questions remain as pressing today as when Black History Month began in Britain in 1987.

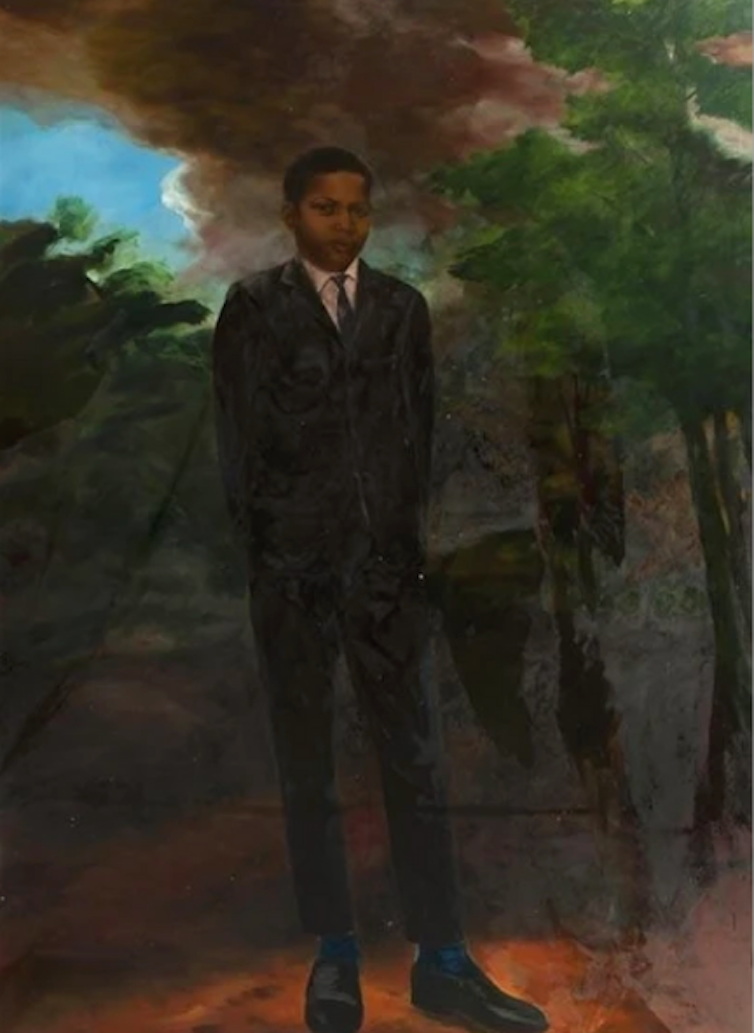

British artist Eugene Palmer’s series of eloquent landscape portrait paintings prove an unlikely source for answers. Produced nearly 30 years ago, Palmer’s paintings retain all their original vitality and power. They exude the artist’s search for identity. But more than a personal quest, they offer a compelling examination of British history.

Eugene Palmer

Now in his mid-60s, with nearly 40 years of painting behind him, Palmer remains one of Britain’s most important if undervalued artists. Although some of his paintings are held in public collections, like the artist himself, they merit far greater exposure – for Palmer’s painting brings much-needed clarity to the often unspoken racial dynamics that underpin British history and society.

Early years

Born in 1955, in Kingston, Jamaica, Palmer would, like many adults and children of his generation, emigrate to Britain. For 11-year-old Palmer, this meant settling down to a new life in Birmingham.

Following his formative period of art education during the 1970s, Palmer established himself as an important painter. He was selected twice for the prestigious The New Contemporaries, an annual touring exhibition for emerging artists. During the 1980s he was included in important exhibitions such as Caribbean Expressions in Britain and Black Art Plotting the Course.

Eugene Palmer

In the early 1990s, Palmer turned certain art and social conventions on their head, embarking on what art historian Eddie Chambers described as “the employment of classically derived aesthetics” which “resulted in a new body of work that was wholly unique amongst Britain’s Black artists”. Palmer challenged a painting tradition primarily constructed around a sense of romanticism, and the mythical notion of true Englishness, with landscape portraits historically used to portray the landowning elite.

Palmer’s more recent work: ‘Didn’t it Rain: New Paintings’, James Hockey Gallery, University for the Creative Arts, 2018 Photo: Steve White.

His subjects were primarily his daughters and younger brother portrayed against luscious landscapes and brooding skies. Paintings such as Lulu Holding Stalks of Wheat (1993) and The Brother (1992) are imbued with a deeply personal dimension.

Others such as The Letter (1992), depicts a man in smart 1950s attire, or the curiously titled Duppy Shadow (1993). Originating from African folklore, “duppy” is a term for a ghost, which is commonly used in Jamaica, illustrating how Palmer draws on aspects of his Jamaican heritage.

These paintings of “ordinary” people exude empathy and grace. Elevating their subjects, they afford Black people the sort of respect and dignity often absent in contemporary British society. Equally, Jamaican art historian Petrine Archer-Straw (1956-2012) noted how Palmer’s paintings built on Ingrid Pollard’s hugely important photographic series Pastoral Interludes from 1987, by exploring “the sense of alienation and displacement” Black people feel in Britain “when confronted with the countryside”.

Legacies of slavery

Because Black people historically settled in Britain’s urban areas, the countryside has been seen as mainly a white person space – or somewhere that is “alien” to Black people. Black people have also been made to feel unwelcome in rural areas and this is one of the reasons why Black people tend to frequent the British countryside less – in the UK, people of BAME background make up only 1% of visitors to national parks, for instance.

But Palmer points out that the countryside is in Black people’s ancestry and so it isn’t an alien space at all. Indeed, Black people and rural areas are irrevocably intertwined by the spectre of slavery. Nowhere was this legacy more evident than in Jamaica.

Eugene Palmer

More significantly for Palmer, such thinking all too conveniently erased the spectre of the plantation from the British consciousness. For these reasons, Palmer’s portraits offer yet another level of meaning. They challenge how the English landscape tradition, like British history itself, remains largely insulated from the spectre of the slave plantation.

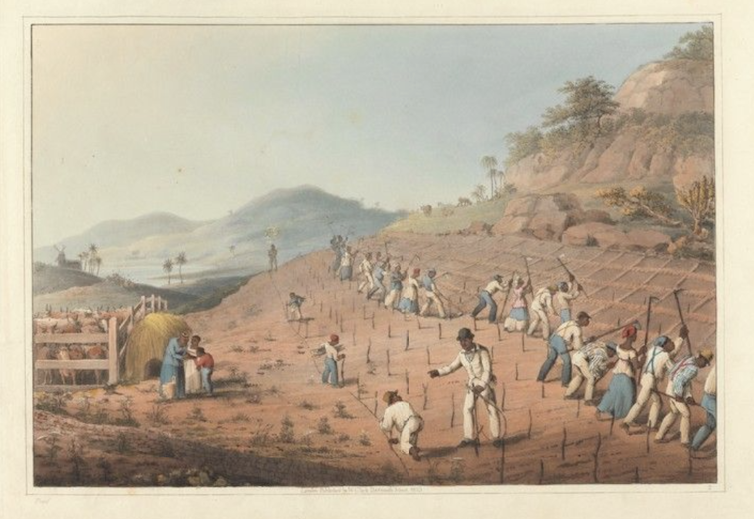

One of the most renowned figures of this tradition is John Constable, whose style is typified by The Hay Wain (1821), which depicts a rural scene on the River Stour between the English counties of Suffolk and Essex. Just two years after this, William Clark produced the idealised drawings Ten Views in the Island Antigua: in which are represented the process of sugar making (1823), which portrays Black slaves working in a rural environment.

These two different countrysides may seem a million miles apart, but both genteel depictions harbour a deception. Where Constable’s painting offers a one-dimensional appreciation of the rural English idyll, Clarke’s work shows slavery hidden in plain sight. In truth, Clarke was sent to create these pictures and present what was happening in a positive light: essentially defending slavery and trying to show people back in Britain that it wasn’t too bad.

John Constable, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By placing the Black subject within the landscape as Palmer does, he asks us to reconsider our assumptions and perceptions. And Palmer’s paintings reveal the extent to which a certain form of selective cultural amnesia continues to govern our understanding of British history.